The ARK origin story

By 2001 there were four major persistent identifier (PID) types, so why was it necessary to create a fifth? The origin story of the fifth type, the Archival Resource Key (ARK), is adapted from this interview in 2021.

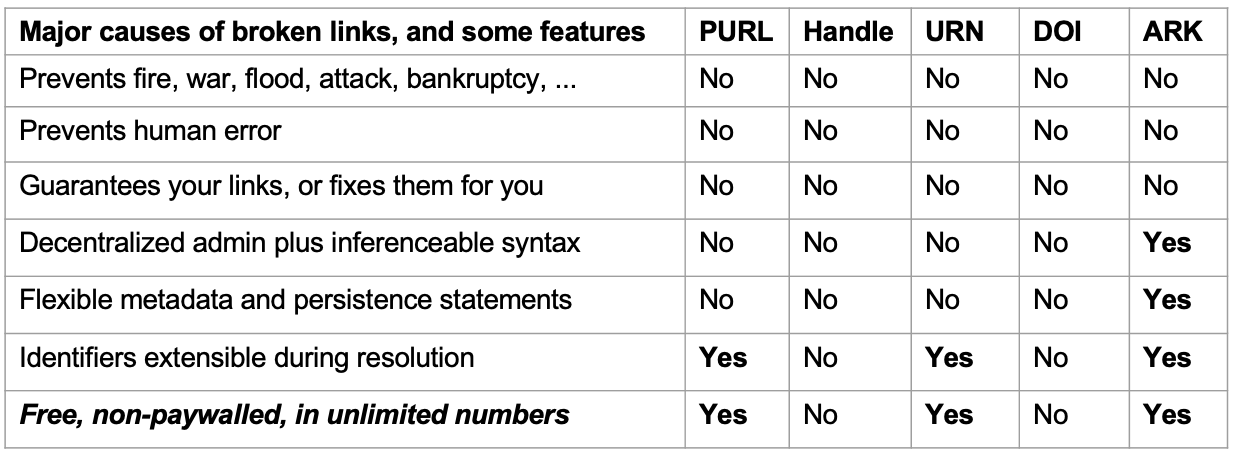

Capabilities defined for five types of persistent identifier (PID).

To explain the need for ARKs is a bit involved and touches on its four predecessor PID schemes: PURL, Handle, URN, DOI. Almost as soon as the Web was created, URLs (web links) were breaking in ways that could be fixed by adding a “web redirect,” which causes an access request to an old URL to be forwarded to a new URL. This is a classic use of “indirection”, so called because when the host at the old URL forwards it, the old URL becomes an indirect link to the new URL. The host named in the old URL – the one that starts the forwarding – is known as the “resolver”.

All the early PID schemes focused on indirection (URL-forwarding). An example is the PURL (Persistent URL) forwarding service. Without charging fees, it allows one to set up indirect URLs based at the PURL.org resolver and to change the target (“new”) URLs as often as needed. The PURL.org hostname was chosen carefully so that it would not have to change. In 1992 the role of that indirect link was abstracted by the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force, the premier Internet standards body) into a new concept: the URN (Uniform Resource Name). The URN was meant to be a persistent link that would resolve to the current best URL. URNs would be as free to create as URLs and would conform to open Internet standards. At the same time, the URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) concept was invented as an umbrella term to mean either URN or URL.

The URN, Handle, and DOI schemes began as what I’ll call URL-forwarders-in-denial. Each scheme promoted specious arguments, claiming

- that indirection is “high-tech” – instead of technically trivial with any off-the-shelf web server,

- that URLs are inherently unreliable – except for their own URLs of course, and

- that its PIDs, not being URLs, were better – except that its PIDs never worked on the open web unless carried inside URLs.

Nonetheless, the mythology of this view took root and continues to recruit paying customers, even though these systems provide much the same service that is offered for free from hundreds of modern URL shorteners. All such systems need one more bit to complete their service: to choose the hostname of the resolver (URL forwarder) carefully, commit to it, and offer it to their customers. Any community can do this for itself.

Another problem is that, while indirection is important for managing links, it only addresses a fraction of the causes of broken links. PID systems all make their customers/curators do the tedious work of creating the indirect link and keeping the URL forwarding information up-to-date, and they do nothing to prevent the major causes of broken links: human error, bankruptcy, fire, war, etc. Any collection or archive will already maintain a list of its objects, and it suffices (after choosing a web server name carefully) to add a parallel list (eg, a new database table column), and to populate it with indirect links that work as web aliases. That collection would then have permalinks (stable URLs) that are as persistent as any PIDs that might be paid for, and that would leave everyone with time and money to attend to the more serious aspects of persistence. Maybe PID systems weren’t even worth the trouble; they were conspicuously absent when Tim Berners-Lee (the inventor of the WWW) wrote the 1998 technical note, “Cool URIs don’t change”.

Each PID system had specific problems. The Handle system was introduced to the IETF and was met with derision and alarm. First, it pretended to be a high-tech solution to a high-tech problem when neither the solution nor the problem was high-tech. Second, it proposed to standardize itself as the sole vendor and gatekeeper of the world’s valuable content (the portion of the web for which people would want persistent links). The WWW had recently revolutionized content dissemination, empowering anyone to be an “electronic publisher”, anywhere, without fees, and without a publishing contract. But the closed-source, fee-based, centralized Handle system would roll back those benefits (just for the most valuable content), metaphorically putting the open-access web genie back in its lamp. Handles are antithetical to an implicit principle that Internet standards must not endorse control by any one entity, over access to the networked resources of another entity.

The free URN scheme had its own problems. It got stalled in the IETF, and along with it, the promise of a free, Internet standard PID that was not a URL. Although people were minting URNs, and URN syntax standards were advancing, no URN resolver discovery service was implemented. As time wore on, it seemed to me that the IETF community lost interest in creating a whole new Internet indirection infrastructure that would add little to existing web and DNS mechanisms, especially in light of the small part that indirection plays in keeping links from breaking. The hypothesis that URNs needed to exist as a vital complement to URLs was failing. (Of course the same was true for Handles and DOIs.) If URNs were always to be carried inside URLs, then they were a subset of URLs. But that would undermine the core URI concept as an umbrella term for URL or URN. The URN may remain stalled until this conceptual conflict is resolved.

The fee-based DOI scheme had its own problems too. While the Handle system was rejected by the IETF, it eventually found a major adopter that was comfortable with paywalls and controlled information access. It was a group of publishers who owned the most profitable, price-gouging academic journals, known for decimating university library budgets and triggering the birth of the oppositional open access movement. Their plan was to use the then new DOI scheme, which was based on the Handle system for URL forwarding, and to target the academic and research communities who depended for career advancement on publishing in their prestigious paywalled journals and on appearing in their proprietary citation databases. Their brand of DOI (CrossRef DOIs) would strengthen this closed infrastructure. DOI recruitment used the same specious arguments as Handle recruitment: DOIs are not URLs but are unbreakable links (like any PID, of course, they break by the thousands and have to be repaired regularly) supported by the “high-tech” Handle system.

To wrap up the story, the ARK scheme was created in 2001 to address these many concerns about the PID landscape. ARKs embraced being URLs, but contain scheme label (“ark:”) similar to URNs (“urn:”), so that, coming across a URL-based ARK in the wild, a recipient can recognize it and conclude that the link is meant to be persistent. In contrast, PURLs have no syntax to distinguish them from the vast majority of URLs that are not meant to last. ARKs are uniquely decentralized so that anyone can assign, steward, and redirect them as freely as URLs. Open source tools allow implementers to be self-sufficient in creating, describing, and resolving ARKs following known practices (eg, opaque identifiers with check digits). Unlike the Handle and DOI systems, they did not use paywalled silos, and they promote linking identifiers to metadata and to commitment statements. ARKs also innovated the idea that persistence is nuanced and can mean different things to different providers.

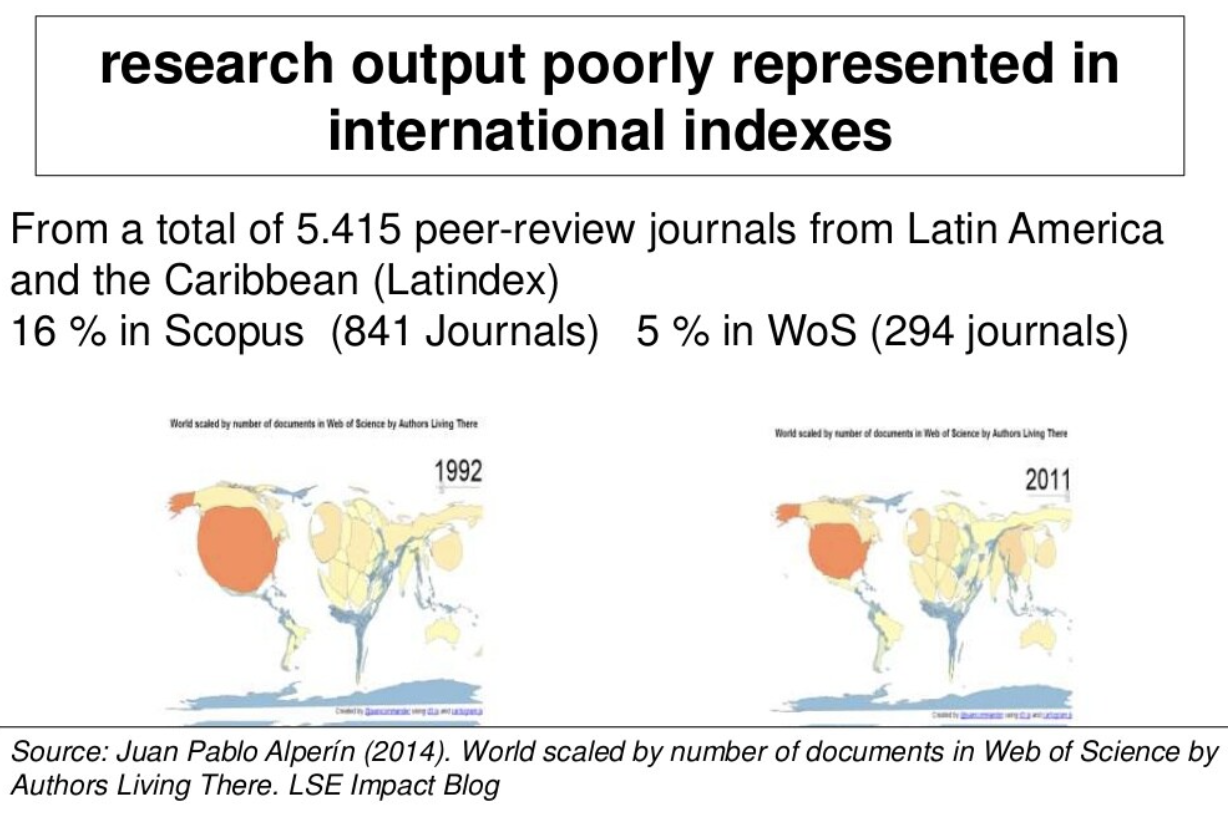

After the passage of two decades, any organization with long-term interests can benefit from ARKs, especially those with budget constraints. A large portion of the world’s research is invisible to the global North because the rest of the world cannot afford to participate in its indexing, identification, and publishing infrastructure. For example, 84% of peer-reviewed Latin American journals in 2014 were not indexed by Scopus or the Web of Science. Fees for creating Handles and DOIs make the hard job of persistence harder. Long term commitment is never free of cost or effort, but no one pays for the right to assign ARKs, which can be especially useful for organizations that need large numbers of PIDs.

Slide credit: Dominique Babini